Wellesley Honors the Legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. in the Classroom

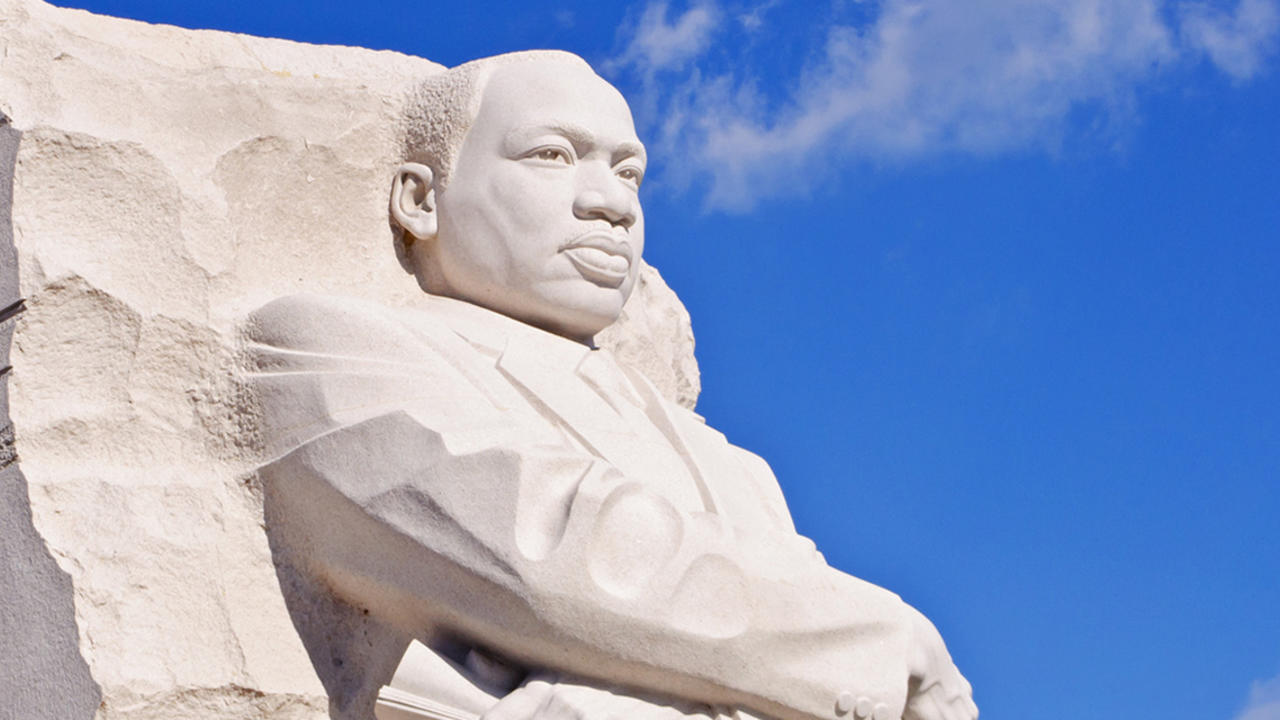

Discussions of race and civil rights remain as relevant today as they were when Martin Luther King Jr. shared his dream with the world in 1963. The country honors King each year with a holiday in his name; at Wellesley, faculty and students study his teachings—and the issues critical to understanding what he fought for—throughout the year.

As a liberal arts college, it should be no surprise that many courses at Wellesley touch upon the topics of race, social justice, inequality, and human rights—though contexts and lenses in a range of subjects, including literature, history, political theory, philosophy and even environmental studies.

In some courses these topics are the central focus, such as Cord Whitaker’s ENG 291: What is Racial Difference and Catia Confortini’s PEAC104: Introduction to the Study of Conflict, Justice and Peace. Laura Grattan’s POL345: Race and Political Theory seminar description lists King among the authors covered.

In Ophera Davis’ AFR 213: Race Relations and Racial Inequality class, King’s philosophy permeates a semester-long study of structural inequality, especially in the United States. Davis said one of her favorite King quotes is, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” She encourages students to reflect on historical, educational, and societal injustice and challenges them to think of contemporary ways to become more engaged citizens.

“As a southerner from the Mississippi Delta,” said Davis, “a key area where King and civil rights workers marched to stop overt injustice such as Jim Crow segregation and voting rights restrictions…I remind students that King dreamed of a post-racial society, where people would ‘not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character..’ I believe that in addition to my classroom responsibilities, I am here to…encourage students to revive and live King’s dream in and outside of the race relations and inequalities course.”

Many courses at the College address African-American history and cultural influences within specific areas of interest. Students may choose AFR222: Blacks and Women in American Cinema or the AFR243: Black Church (both with Pashington Obeng), as well as AFR266: Black Drama or AFR 320: Blackness in the American Literary Imagination (both with Selwyn Cudjoe). Multiple courses, including Lindsey Stewart’s Black Feminist Philosophy class (cross-listed in Africana studies and philosophy) address the interplay of race and gender. Race and its intersection with other social constructs are also included in, but are not limited to, classes on family life, medicine, politics, and education.

Other courses explore race and civil rights in ways that may not be apparent from course titles but are integral to a comprehensive study of the subject. For example, James Turner references environmental justice as central to environmental studies, and discusses how environmental activism is shaped by race, gender, and/or nature in ES203: Culture of Environmentalism. In her course WGST240: U.S. Public Health, which she said “understands public health as philosophically rooted in a commitment to social justice,” Charlene Galarneau references this King quote, from the 1966 Medical Committee for Human Rights convention: “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and inhuman.”

King’s legacy is also evident on a more personal level, within the context of students’ and faculty’s own life experiences. Adam Van Arsdale, whose anthropology courses include discussions of race, social roles, and human rights, shared his own familial connection to King: “[Martin Luther King Jr.] was a hero of my grandfather, who was a very social justice minded pastor. My own father submitted his application to seminary the day after [King] was shot, following in his father’s footsteps. While I am not drawn to the same ministerial calling, social justice remains an important part of my calling in education.”

King himself examined education in a 1947 paper he authored as student at Morehouse College entitled “The Purpose of Education.” He wrote, “We must remember that intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education. The complete education gives one not only power of concentration, but worthy objectives upon which to concentrate. The broad education will, therefore, transmit to one not only the accumulated knowledge of the race but also the accumulated experience of social living.”